Museo y memorial abierto para recordar a los asesinados en violencia racial

Por C. S. Satterwhite

MONTGOMERY, Ala.—The Legacy Museum (El Museo del Legado) y el National Memorial for Peace and Justice (Memorial Nacional para la Paz y Justicia) se inauguró recientemente en Montgomery, Ala., a la emocion internacional. Ambos espacios ofrecen una perspectiva atrasada sobre el problema de larga data de los Estados Unidos con el racismo y el terrorismo racial, confrontando a los dos y conectandose con nuestro entorno racial actual.

Tanto el museo como el monumento están patrocinados por la Equal Justice Initiative (Iniciativa de Igualdad de Justicia, o EJI) de Montgomery, una organización sin fines de lucro cuya misión es desafiar la pobreza y la injusticia racial al tiempo que promueve la igualdad de trato en el sistema de justicia penal. El monumento y el museo están forzando una conversación nacional sobre la esclavitud y el linchamiento mientras demuestran los efectos persistentes en las comunidades minoritarias, incluida la disparidad económica, los crímenes de odio, las leyes de supresión de votantes, las políticas antiinmigración y el encarcelamiento masivo.

The Legacy Museum cubre la historia de la esclavitud en los Estados Unidos, con un enfoque específico en el comercio doméstico de esclavos, trazando paralelismos con el racismo en el sistema de justicia penal. Impresionante por su alcance y tecnología, el Legacy Museum se encuentra en un antiguo almacén donde los sureños blancos compraron esclavos africanos en una subasta antes de la Guerra Civil.

A pocos pasos de la puerta de entrada, los visitantes se enfrentan a hologramas fantasmales de africanos esclavizados tras las rejas. Los hologramas realistas e inquietantes incluyen una figura más antigua que ofrece consejos a otras personas esclavizadas, mujeres que lamentan la pérdida de sus hijos y niños solitarios que lloran por sus madres.

Después de salir de la prisión esclava recreada, los visitantes ven una pared de anuncios para la venta de seres humanos y las imágenes de la segregación. Otra faceta tecnológica del museo es un puesto virtual de visitas a las prisiones donde los presos recientemente liberados cuentan sus historias de injusticia.

La visita autoguiada se cierra con una pared de jarrones que conmemora a los afroamericanos linchados. El linchamiento de los afroamericanos en el sur fue generalizado y comenzó como un medio para aterrorizar a las comunidades negras a medida que comenzaron a obtener derechos políticos. Los frascos contienen tierra de los sitios de un linchamiento con el nombre de la persona linchada.

A un corto paseo del Legacy Museum se encuentra el National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

El monumento reconoce a los hombres y mujeres linchados en el sur de Estados Unidos en los años que transcurrieron entre la Guerra Civil y la Segunda Guerra Mundial.

A mediados de la década de 1940, las turbas blancas asesinaron a más de cuatro mil afroamericanos con actos tan atroces como torturas, quemaduras, desmembramientos y, sobre todo, ahorcamientos. La mayoría de los condados del sur tenían al menos un linchamiento, y algunos tenían muchos.

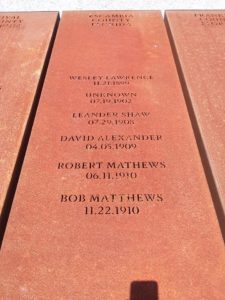

Por ejemplo, cientos de ciudadanos blancos en el condado de Escambia participaron en el linchamiento de al menos seis hombres afroamericanos. Dos hombres, Leander Shaw y David Alexander, fueron linchados en Plaza Ferdinand, en el corazón de Pensacola. Otro fue linchado afuera de un tren en movimiento cerca de la actual Scenic Highway. Un hombre, un “negro sin nombre”, fue linchado al norte de Cantonment.

Todos los linchados en el condado de Escambia, Fla. son recordados en este monumento.

Para muchas de las personas recordadas en el Memorial for Peace and Justice, sus ofensas fueron menores. Los blancos lincharon a un hombre por llamar a la puerta de una mujer blanca, a otro por no haberse dirigido a un oficial de policía como “señor,” y a una mujer por regañar a niños blancos por arrojar piedras.

El sitio principal contiene cientos de grandes monumentos rectangulares oxidados que cuelgan del techo para simbolizar a las personas ahorcadas. Los visitantes caminan más allá y debajo de los monumentos conmemorativos con los nombres de los condados y los nombres de sus víctimas grabados al costado. Fuera de los monumentos colgantes hay réplicas de la que está dentro del área principal. El propósito de los memoriales externos es que cada condado enumerado pueda llevar su monumento a su hogar para mostrarlo públicamente y recordar a estas víctimas del terrorismo racial.

Hasta la fecha, ningún condado ha llevado su marcador a casa.

La intención expresa del museo y del monumento es hacer que los estadounidenses vean la historia racista de los Estados Unidos como vinculada al estado actual de intolerancia, xenofobia y encarcelamiento masivo.

“No hemos creado espacios en este país que cuenten la historia de la desigualdad racial, de la esclavitud, del linchamiento, de la segregación que motive a la gente a decir, ‘Nunca más’,” dijo Bryan Stevenson, director ejecutivo de EJI.

Si bien la historia dolorosa o el terrorismo racial rara vez se reconoce en público, a pesar de ser muy común en todo el sur, EJI espera que las discusiones provocadas por su museo y monumento conduzcan a un futuro más equitativo para todos los que viven en este país.

Museum and memorial open to remember those killed in racial violence

By C. S. Satterwhite

MONTGOMERY, Ala.—The Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice recently opened in Montgomery, Ala. to international fanfare. Both spaces offer an overdue perspective on America’s longstanding problem with racism and racial terrorism, confronting both head-on and drawing connections to our current racial environment.

Both the museum and memorial are sponsored by Montgomery’s Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a non-profit organization whose mission is to challenge poverty and racial injustice while advocating for equal treatment in the criminal justice system. The memorial and museum are forcing a nation-wide conversation about slavery and lynching while demonstrating the lingering effects throughout minority communities, including economic disparity, hate crimes, voter suppression laws, anti-immigration policies, and mass incarceration.

The Legacy Museum covers the history of slavery in the United States, with a specific focus on the domestic slave trade, drawing parallels to racism in the criminal justice system. Impressive for its scope and technology, the Legacy Museum sits in a former warehouse where white Southerners purchased enslaved Africans at auction before the Civil War.

Within a few steps of the front door, visitors face ghost-like holograms of enslaved Africans behind bars. The realistic and haunting holograms include an older figure offering advice to others enslaved, women lamenting the loss of their children, and lone children crying for their mothers.

After walking out of the recreated slave prison, visitors see a wall of advertisements for the sale of human beings and images from segregation. Another technological facet of the museum is a virtual prison visitation booth where recently released prisoners tell their stories of injustice.

The self-guided tour closes with a wall of jars memorializing African Americans lynched. The lynching of African Americans in the South was widespread and began as a means to terrorize black communities as they started to gain political rights. The jars contain dirt from the sites of a lynching with the name of the person lynched.

A short walk from the Legacy Museum is the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

The memorial recognizes the men and women lynched in the American South in the years between the Civil War up until World War II.

By the mid-1940s, white mobs murdered more than four thousand African Americans by acts as heinous as torture, burnings, dismemberments, and most notably hangings. Most counties in the South had at least one lynching, with some having numerous.

For instance, hundreds of white citizens in Escambia County participated the lynching of at least six African American men. Two men, Leander Shaw and David Alexander, were lynched in Plaza Ferdinand located in the heart of Pensacola. Another was lynched outside of a moving train near the present-day Scenic Highway. One man, an “unnamed negro,” was lynched north of Cantonment.

All of those lynched in Escambia County, Fla. are remembered at this memorial.

For many of the people remembered at the Memorial for Peace and Justice, their offences were minor. Whites lynched one man for knocking on a white woman’s front door, another for not addressing a police officer as “sir,” and one woman for scolding white children for throwing rocks.

The main site holds hundreds of large rusted rectangular memorials hanging from the ceiling to symbolize the people hanged. Visitors walk past and below memorials with the names of counties and their victims’ names etched on the side. Outside of the hanging memorials are replicas of the one inside the main area. The purpose for outside memorials is so each county listed could eventually bring their memorial home to display publicly and remember these victims of racial terrorism.

To date, no county has taken their marker home.

The expressed intent of the museum and memorial are to make Americans see the racist history of the U.S. as linked to the current state of bigotry, xenophobia and mass incarceration.

“We haven’t created spaces in this country that tell the history of racial inequality, of slavery, of lynching, of segregation that motivate people to say, ‘Never again’,” said Bryan Stevenson, the executive director of EJI.

While the painful history or racial terrorism is rarely recognized in public, despite being very common throughout the South, EJI hopes the discussions provoked by their museum and memorial will lead to a more equitable future for everyone living in this country.